I recently had the privilege of attending Chris Miller’s presentation and fireside chat at the Northern Virginia Technology Council (NVTC) event, and I can honestly say it was one of the most eye-opening experiences I’ve had in years. Standing in the heart of one of America’s technology hubs, listening to Miller articulate the high-stakes drama unfolding in the semiconductor industry, I realized we’re living through a geopolitical transformation as consequential as the Cold War—only this time, the battlefield is measured in nanometers, not kilometers.

Miller’s book, Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, isn’t just another tech history. It’s a masterfully crafted narrative that reads like a thriller while delivering profound insights into how these tiny pieces of silicon have become the foundation of modern power itself. After reading the book and hearing Chris speak, I wanted to share my thoughts on this genuinely extraordinary work—all credit goes to Chris Miller for this important contribution to our understanding of technology and geopolitics.

From Vacuum Tubes to Nanometer Precision: The Revolution That Changed Everything

What struck me most powerfully, both in the book and at the NVTC event, was Miller’s ability to trace the semiconductor’s journey from a laboratory curiosity to the most strategic resource on the planet. The story begins in 1958, when Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments and Bob Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor independently invented the integrated circuit. At that moment, the cutting edge meant cramming just four transistors onto a single chip. Today, Apple’s processors contain 11.8 billion transistors, each smaller than a coronavirus.

Think about that for a moment. In 2020, for just the iPhone 12 alone, TSMC’s Fab 18 fabricated over one quintillion transistors—a number with eighteen zeros.

Nothing else even comes close.

The transformation wasn’t just technological—it was fundamentally geopolitical. World War II was decided by steel and aluminum, Miller argues. The Cold War was defined by atomic weapons. But the rivalry between the United States and China may well be determined by computing power. This insight crystallized for me during the NVTC event when Chris described how precision-guided weapons transformed American military doctrine, turning conflicts from wars of industrial attrition into demonstrations of technological supremacy.

The Unlikely Heroes: Morris Chang and the Taiwan Miracle

One of the book’s most compelling narratives centers on Morris Chang, the founder of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Chang’s life story reads like something from a Hollywood screenplay. Born in mainland China, he survived World War II by fleeing Japanese armies across multiple cities. He was educated at Harvard, MIT, and Stanford. He worked for Texas Instruments in Dallas, where he held top-secret U.S. security clearance to develop electronics for the American military.

When Texas Instruments passed him over for the CEO position in the 1980s, Taiwan’s government offered him something no American company would: a blank check to build the island’s semiconductor industry. Chang’s response was revolutionary. He created the foundry model—a company that would manufacture chips designed by others but would never compete with its own customers by designing chips itself.

Miller explains how Chang pitched this idea to his former colleagues at Texas Instruments as early as 1976, predicting that “the low cost of computing power will open up a wealth of applications that are not now served by semiconductors”. Intel’s Gordon Moore told him bluntly: “Morris, you’ve had a lot of good ideas in your time. This isn’t one of them”.

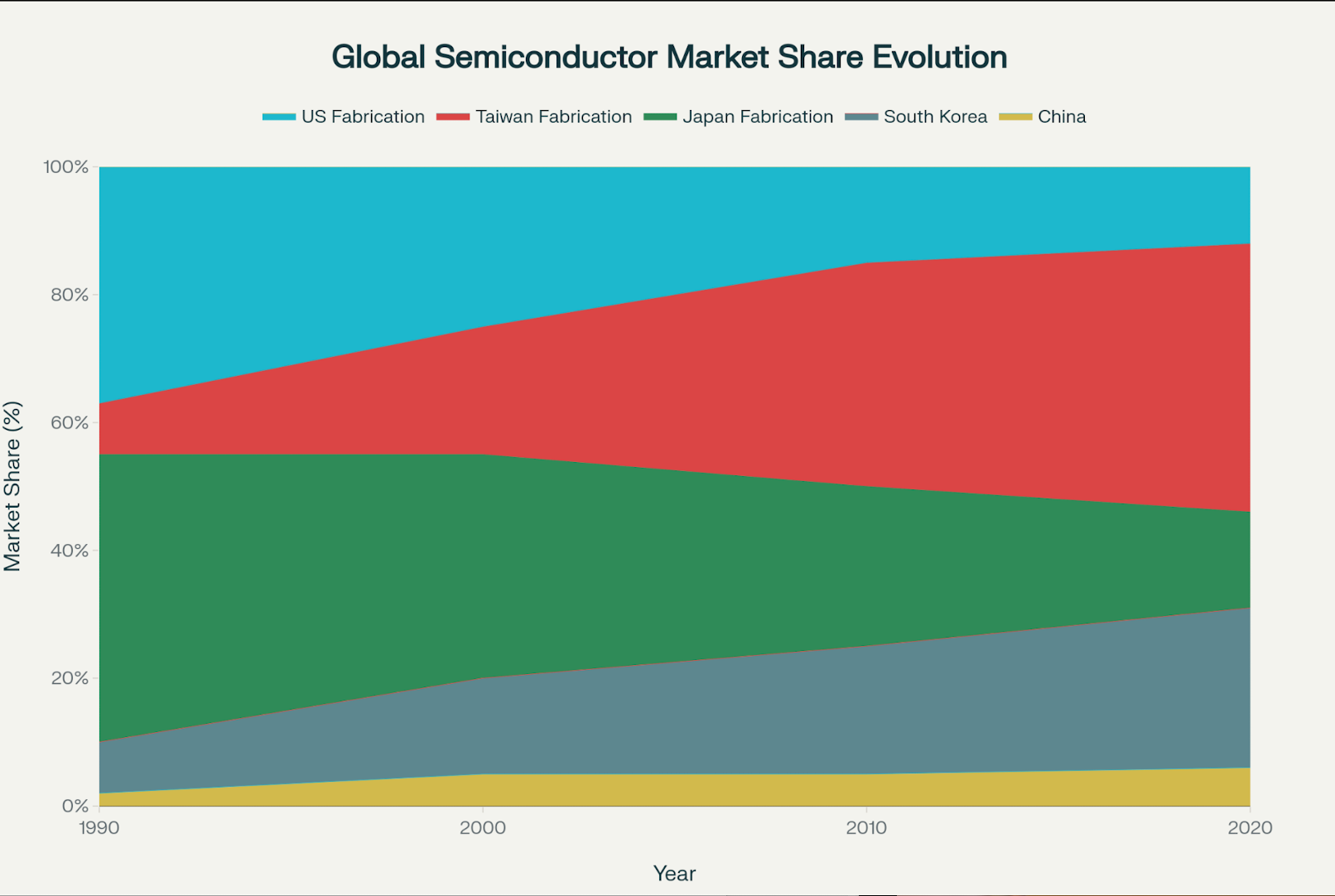

Moore was spectacularly wrong. TSMC grew to dominate the foundry business, producing chips that power iPhones, data centers, and advanced AI systems. By 2020, TSMC was fabricating chips that produce 37% of the world’s new computing power each year. The company’s most advanced facility can etch features smaller than half the size of a coronavirus—a hundredth the size of a mitochondria.

What makes TSMC’s dominance particularly fascinating—and frightening—is its geographic concentration. As Miller emphasizes, Taiwan sits atop a major fault line, and the island that Beijing considers a renegade province has become indispensable to the global economy. A single missile strike on TSMC’s most advanced fabrication facility could cause hundreds of billions of dollars in damage once you account for delays in producing phones, data centers, automobiles, and other technology.

The Choke Points: Where Power Really Lies

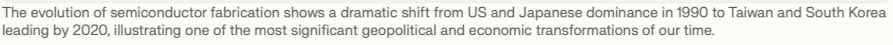

During his NVTC presentation, Chris Miller made a point that has stayed with me: we often hear that “data is the new oil,” but the real limitation we face isn’t the availability of data but of processing power. There’s a finite number of semiconductors that can store and process data, and producing them depends on a series of unprecedented choke points.

Consider extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines. These devices, which cost over $100 million each and are built from hundreds of thousands of components, are produced by exactly one company: ASML in the Netherlands. Without EUV machines, cutting-edge chips are simply impossible to make. ASML builds 100% of the world’s EUV lithography machines—OPEC’s 40% share of world oil production looks unimpressive by comparison.

The book details how this monopoly emerged through a combination of technological brilliance, strategic partnerships, and the failure of American competitors. GCA, once America’s lithography leader, collapsed due to mismanagement and arrogance toward customers. Japanese firms like Nikon and Canon dominated for a time but missed the shift to EUV technology. ASML survived as a scrappy Dutch startup through deep partnerships with chipmakers like TSMC and Intel, eventually receiving billions in direct investment from these companies to ensure EUV development continued.

The concentration of power extends beyond lithography. Two South Korean companies—Samsung and SK Hynix—produce 44% of the world’s memory chips. American companies Synopsys and Cadence control about 75% of the electronic design automation (EDA) software market, without which modern chip design is impossible. And sitting at the center of this web is Taiwan, producing chips that power everything from smartphones to missile guidance systems.

China’s Desperate Quest and America’s Complacency

Perhaps the most urgent theme in Chip War is China’s multi-decade struggle to achieve semiconductor self-sufficiency—and why it keeps falling short. Miller traces this journey from Mao Zedong’s disastrous Cultural Revolution, when scientists were sent to work on peasant farms while the chairman’s supporters insisted that “all people must make semiconductors”, to Xi Jinping’s massive subsidies pouring billions into chip companies today.

The irony is painful. When the integrated circuit was invented in 1958, China had many advantages: a vast, low-cost workforce and a well-educated scientific elite. But Communist paranoia about foreign influence and Mao’s war on expertise destroyed these advantages. While Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore were attracting American semiconductor investment in the 1960s and 1970s, China was plunging into revolutionary chaos.

Today, China spends more money importing chips than it spends on oil. This dependence terrifies Beijing’s leadership. As Miller documents, when the U.S. placed Huawei on the Entity List in 2020, barring the company from buying advanced chips made with American technology, Huawei’s global expansion ground to a halt, entire product lines became impossible to produce, and revenue slumped. The corporate giant faced “technological asphyxiation”.

Recent reports suggest China has made impressive progress in some areas. SMIC, China’s leading foundry, reportedly achieved 5-nanometer chip production without EUV lithography—something most experts thought nearly impossible. But look closer at the details, and the picture is less impressive. SMIC’s 5nm yield is about one-third that of TSMC’s equivalent, with costs estimated to be 40-50% higher. It’s not commercially scalable, and the company remains years behind in developing 3nm and 2nm processes.

China’s challenge isn’t just technological—it’s systemic. The country faces critical gaps in cutting-edge lithography, chronic talent shortages (a predicted deficit of 200,000 to 250,000 specialists by 2027), and continued dependence on foreign components even in its most advanced chips. Despite massive government subsidies exceeding $150 billion through various initiatives like “Made in China 2025,” China will likely achieve only 30% self-sufficiency by the end of 2025—far short of its 70% goal.

My Reflections: The Chip War Enters a Dangerous Phase

Listening to Chris Miller speak at the NVTC event, I was struck by how much the situation has evolved even since the book’s publication in 2022. The semiconductor industry now sits at the intersection of three mega-trends: artificial intelligence, geopolitical competition, and supply chain vulnerability. Each amplifies the others in potentially catastrophic ways.

The AI revolution has made advanced chips more strategically important than ever. As Miller noted during his keynote, computing power is key not just to the future of our economy as we develop artificial intelligence but also central to the deployment of national power on the international stage. Nvidia’s dominance in AI accelerators, TSMC’s monopoly on manufacturing them, and China’s desperate efforts to develop alternatives create a tinderbox of competing interests.

The geopolitical dimension grows more fraught by the day. Recent estimates suggest that a full-scale conflict over Taiwan could result in a $10 trillion loss to the global economy—even a blockade scenario would cost $2.7 trillion. China’s economy would shrink by an estimated 7%, and Taiwan’s by nearly 40% in the first year alone. These figures dwarf the economic cost of the war in Ukraine, which remains under $250 billion.

What worries me most is the short-term vulnerability. Taiwan’s semiconductor supply chain is particularly susceptible to a Chinese quarantine before 2027, according to scenario analyses. The commonly debated resilience strategies—diversification and stockpiling—are better suited for long-term solutions and may not effectively ensure resilience in the immediate term. While TSMC is building facilities in Arizona, Japan, and Europe, Taiwan’s government mandates that cutting-edge work remain on the island. Geopolitical risks will continue to be critical for the foreseeable future.

The American Response: Too Little, Too Late?

Miller’s book chronicles how American complacency contributed to the current crisis. In the 1990s, as globalization became gospel and the “unipolar moment” seemed to vindicate American power, policymakers waved through decisions that would prove consequential. When ASML bought Silicon Valley Group (SVG), America’s last major lithography firm, in 2001, hardly anyone in Washington was concerned. The dominant belief was that expanding trade and supply chain connections would promote peace.

The 2022 CHIPS Act, which provides $52 billion in subsidies to boost American semiconductor manufacturing, represents a belated recognition of these mistakes. But as experts note, building resilience is both time-consuming and costly, with cutting-edge manufacturing plants costing around $20 billion each. It may take a decade for the U.S. to increase its share of the global chip market from 10% to just 15%.

Meanwhile, the industry continues its relentless evolution. Moore’s Law—the prediction that computing power doubles roughly every two years—has been declared dead many times, yet keeps defying the skeptics. New transistor architectures like gate-all-around, advanced packaging techniques, and novel computing paradigms continue pushing the boundaries. As Miller documents, we’re not running out of atoms—we know how to print single layers of atoms, and there’s more money than ever flowing into chip innovation.

Lessons for the Future

Reading Chip War and experiencing Chris Miller’s presentation left me with several conclusions about our technological and geopolitical future:

First, concentration breeds vulnerability. The semiconductor supply chain’s efficiency came at the cost of resilience. When a handful of companies in a few geographic locations control technologies essential to modern civilization, a single earthquake, political crisis, or military conflict can cascade into global catastrophe.

Second, technological leadership requires sustained commitment. America’s dominance in semiconductors emerged from decades of government research funding, world-class universities, venture capital ecosystems, and the largest consumer market. That lead wasn’t inevitable—it required deliberate choices and continuous investment. It can be lost through complacency or regained through determination.

Third, the private sector must lead, but government has a crucial role. As Miller emphasized during the NVTC event, private companies have visibility into their operations that governments lack. But governments can fund basic research, provide incentives for domestic production, and coordinate responses to strategic threats. The most successful chip industries—whether in Taiwan, South Korea, or historically in the United States—have always involved public-private partnerships.

Fourth, China’s challenge is immense but not insurmountable. The country has made remarkable progress under intense pressure, demonstrating impressive innovation capacity. However, the gap in cutting-edge lithography, talent shortages, and dependence on foreign equipment and materials represent fundamental obstacles that subsidies alone cannot overcome. China is likely to achieve significant self-sufficiency in mature and moderately advanced nodes, but the race for the absolute leading edge will remain fiercely competitive.

Finally, the chip war is ultimately about power in its most fundamental sense. Control over semiconductor technology determines who leads in artificial intelligence, who dominates military capabilities, and whose economy thrives in the 21st century. As Miller argues compellingly, semiconductors have defined the world we live in, determining the shape of international politics, the structure of the world economy, and the balance of military power.

A Must-Read for Our Time

Chip War is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand our technological and geopolitical moment. Miller has crafted a narrative that’s simultaneously a history of innovation, a business drama, and a warning about the future. The book works because it recognizes that semiconductors aren’t just about technology—they’re about the people who invented them, the companies that commercialized them, the governments that supported or hindered them, and the global competition that now threatens to fracture the industry.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough. Whether you’re a technology professional, a policymaker, an investor, or simply a citizen trying to understand the forces shaping our world, Chip War provides indispensable context and insight. Chris Miller has given us a masterwork of historical and geopolitical analysis, and his NVTC presentation only reinforced how urgent these issues have become.

As we navigate an era where computing power determines national power, where supply chains double as geopolitical weapons, and where the world’s most advanced technology depends on a small island in one of the world’s most dangerous political disputes, we desperately need the clarity and perspective that Miller provides. The chip war is far from over—in many ways, it’s just beginning. Understanding how we got here is the first step toward navigating where we’re going.

Buy your own copy of the book here.

Disclaimer: This blog post is a personal review and commentary on Chris Miller’s book “Chip War.” All insights, historical narratives, and analysis discussed are drawn from Miller’s research and work. I make no claim to the original research or conclusions—those belong entirely to Chris Miller and are used here for educational and review purposes.